When Pete Buttigieg, the nation’s first truly viable gay presidential candidate, launched his campaign earlier this year, he did so from his home in South Bend, Indiana, one of the reddest states in the country.

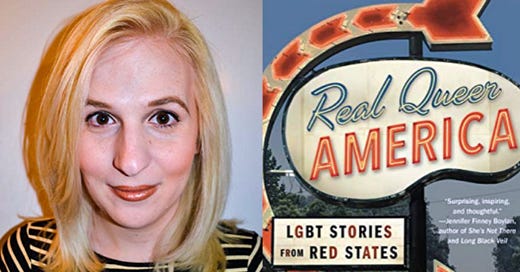

But what does his being from a red state mean? What is life like for queer people living in so-called “Trump Country”? There’s no one better positioned to contextualize LGBTQ life in red states than journalist Samantha Allen, Ph.D., the author of the new book Real Queer America.

Starting in Provo, Utah, Allen embarked on a six-week cross-country road trip documenting the lives of LGBTQ people in Utah, Tennessee, Georgia, and Indiana among others.

What follows below is a wide-ranging conversation with her regarding her findings, Pete Buttigieg, religious freedom and LGBTQ rights, red-state boycotts, and the life-giving magic of road trips.

Interview is slightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Leigh Ann Carey: You wrote, “This is such a beautifully weird country. I would even call it a queer one.” Given your travels and experiences living in places like Provo, Utah and Bloomington, Indiana, do you think this beautifully weird country is ready to elect a gay president, whether it be Pete Buttigieg or someone else later on?

Samantha Allen: It's really interesting. When I started my book tour, I don't think anyone knew Pete Buttigieg’s name. And now at every reading or signing, when the Q&A portion starts, he’s the first question. Everyone wants to talk about him.

Given the themes of the book, I’m happy for folks who are now realizing for the first time that LGBT people live in places like South Bend, Indiana and can rise to levels of leadership in places that they assumed were really hostile to LGBT people.

Even eight years ago, I couldn't imagine a candidate like Pete Buttigieg even being seen as viable or earning some of the praise from the right that he has. We've crossed a pretty huge turning point. We can stop worrying about whether a gay presidential candidate has a chance, because I think clearly now one does.

How big of a chance is debatable. I spent a lot of time looking at public opinion polling for my book. My impression is that we've got about a third of folks in this country who are staunchly opposed to LGBT rights.

But that doesn't mean that we've got 70% incredibly vocal support. We're badly in need of a moment where that 70% sits down with friends and family and has a conversation like, “Hey, are you cool with LGBT rights? Because I am.”

LAC: When you say America is queer, what does that mean to you in your understanding of queerness?

SA: At the risk of sounding almost mystical about it, to me queerness isn't so much about a specific set of sexual orientations. It’s more of an attitude, or a positionality, a kind of bucking against the norm, but also being quietly confident and living a life that doesn't look like everyone else's.

LAC: Where do you think Buttigieg’s campaign fits within larger narratives around LGBTQ people? Where might his campaign be challenging existing media narratives, and maybe taking those narratives in unexpected directions?

SA: Two things: I'm really interested in the effect that he's had on the discourse around LGBTQ rights and religion. Because he's a proud Episcopalian, he’s talked more about religion than I think any candidate has in like the last two election cycles. He's very vocal about his belief in God, and his belief in God coincides with rather than contradicts his sexual orientation. Amazingly, it seems to be working.

For so long in this country, we've thought of LGBT issues and religious freedom as being these, separate boxes in different corners of the ring duking it out. And for Pete Buttigieg to stand up and say, “I’m a gay Christian,” taking it on like that I think is remarkable. Because while LGBT Americans are generally less religious, a large percentage of us still do profess a faith. I like that he's taken what is a binary conversation and diffused it. Those things are separate and apart from any feelings that I have about him as a candidate.

LAC: What do you make of the debate within the LGBTQ community about Pete Buttigieg and whether or not his candidacy represents progress for queer people?

SA: Pete Buttigieg is mixing with a more mainstream crowd very successfully, and he’s being cast with representing a community that includes folks who simply can’t access those same spheres. There are folks who can't assimilate. When you're a trans woman of color your options for assimilating into existing groups are a lot less than they are if you are cis-gender and a white gay person.

There is a tension in our community: assimilation vs a more radical approach. It's been with our community from the very beginning. Look at homophile societies versus the Stonewall Riots. It’s not a tension that's really going to go away.

As assimilation into existing communities becomes more of an option there are going to be a lot of bumps in the road and a lot of difficult conversations to have there. The conversation that folks are having around Buttigieg is just the start.

LAC: Some folks think Buttigieg’s sexuality has been talked about too much already. But what I've wondered is why we haven't talked to the other candidates about their sexuality at all.

We know if candidates are married, single, or divorced. But reporters don’t ask heterosexual candidates about the moment when they knew they were straight, or when they started to have a sense of their own sexuality. I’d like to know what about masculinity, especially now in the age of #MeToo, is appealing to straight women? I’d like insights into their relationship with their husbands and dealing with power dynamics in an intimate sphere.

How can we talk to the non-queer candidates about their sexuality in ways that would not be invasive but help us understand them and ourselves more?

SA: You make me think about reading The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir. One of the key insights in that text is women are the marked gender and men are perceived as the default. And you see that happen with coverage of female political candidates because folks want to ask questions like, “ is the country ready for a woman president? Or, how do you feel about potentially being the first woman president?”

There's an onus that's placed on people when you belong to a marked gender or sexual orientation something that's not seen as the default. I think you're right that some of the ways to correct that are to stop treating the default as the default to ask a candidate like Joe Biden what does masculinity mean to you? Or, what does it mean to you to be a man trying to run the country in a long, long, long, uninterrupted line of men running the country. You can do a similar thing around orientation. All those questions seem harder to ask, almost.

Simply refusing to treat the default as default would be helpful for our discourse around identity and seeking political office. Because I think too often, you know, candidates like Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris and last cycle Clinton have to both advance policy proposals, compete with male candidates, and reassure the country that the country is ready for women run it. That's a lot to put on someone's plate.

LAC: For folks who’ve never lived in a red state, or it has been a while, what do you hope your book conveys to them about the LGBTQ people living there?

SA: I am trying to challenge the instinct to throw the baby out with the bathwater, to counter the idea that a whole state or whole region or part of the country is just irredeemable because of what some state legislators do.

When you're LGBT in these places, or you're a woman dealing with abortion restrictions it's not like you spend most of your time thinking all of Alabama is garbage. You can't help but love some of the places that you grow up in and the places that shaped you.

For me, that's Provo, Utah. I really wanted to get out of Provo, Utah when I lived in Provo. And I did, but I also really liked Provo and loved the mountains and the old fashioned burger places and the weird bowling alley in the basement of the Student Center at Brigham Young University. So many queer people I know have a similar relationship to their hometown, or a place where they spent a lot of formative time. Maybe they felt oppressed, scared, marginalized, but they also loved the place.

And Kayley, who I wrote about in the book, really spoke to that beautifully with her feelings for Mississippi. She’s not going to say that she hates Mississippi because of what her state’s legislators do. Instead, you show up and protest until those legislators don't have jobs anymore. For someone like Kayley, Mississippi is worth saving. And I think for so many folks living in red states, they live there for a reason. They don't want to have the kind of life that you have in a big coastal blue state city. They want their life in the state they are in, and they’re willing to fight for the quality of it.

LAC: You mentioned in your book, that red state queer folks feel disconnected from mainstream activism culturally and financially. Could you speak more to these divides?

SA: There is a sense of disconnection from the places where large LGBTQ nonprofits are headquartered like in Washington, D.C. Nearly 4 million LGBT adults live in the South. It's one of the largest LGBT populations by region out of any of the in the country. Yet, the South doesn't receive a proportionate amount of LGBT funding.

Since the legalization of same sex marriage, we’ve seen some of the larger national LGBT nonprofits begin turning their attention to southern states and sometimes towards the fights of anti LGBT legislation and ordinances on a local level to protect LGBT people.

The LGBT activists on the ground in these states have been doing this work for decades versus large national groups that were really focused on the brass ring of marriage and are now shifting gears. So, that’s part of the isolation or disconnection.

People feel people feel disconnected or isolated from what's happening in DC for all sorts of reasons. And sometimes this can be for terrible reactionary reasons. But in the case of the LGBT community, I think it's a very valid and justified one.

There have been situations I've mentioned briefly in the book like the HERO (Houston Equal Rights Ordinance) situation in Houston with this equal rights ordinance that got passed and then rolled back at the voter box. There's frustration on the ground there. Local activists spearheaded the resistance to stop the repeal of that law. The activists wanted to put trans voices front and center. And from what folks there told me, there was some hesitancy from the national group to do that, because the national group thought that what people are afraid of is trans people. So we can't have the campaign be about trans people, and we need to make it about something else like equal protection.

And so HERO got repealed. A lot of trans activists on the ground told me that people didn't really know what the ordinance was about. There weren't local trans people front and center owning the issue. So you have little scuffles like this sometimes with national groups who have certain strategies. The local groups who are like we live here and know what works.

LAC: Along those lines, we're talking in the wake of anti-abortion legislation in Alabama and Georgia and the subsequent calls for boycotts of those states. What do you think about this particular tactic? And what is your sense of how people in red state LGBT communities feel about state boycotts?

SA: The tactic of boycotting a red state because they passed a law that you don't like is ill advised and hurtful. There's this tendency and it happens around abortion and LGBT issues where people outside the state equate bad legislation as the failings of the entire state. And what you're talking about is a very specific set of state legislators who are influenced by a very powerful lobby who wants to keep satisfied a very small portion of their party who functions as their base in primary elections. We’re not talking about everyone in the state.

When you boycott a state, you punish everyone in the state. In the case of boycotting over LGBT issues, there are a lot of LGBTQ small business owners in these states. Owning and operating a small business is really hard. It gets even harder when the conference you rely on for 15% of your revenue every year decides to relocate to punish your state over something you had no control over and tried to prevent. They're women living in Alabama and Georgia who need the influx of money that comes into the states, especially as Alabama is already struggling so much economically. It's counterproductive to punish some of the people who are most affected by the law.

LAC: What are the broader lessons LGTQ folks in red states can teach activists on the left and to a very polarized country?

SA: So much change around LGBT issues happens in red states via proximity. Everyone is next to each other going to the same churches or community meetings or restaurants even. You have to bring everybody along on the issue together. And it takes a lot longer than it does in say a big city where everyone can just move there and make politics really progressive and radical.

But I feel like the change that does happen in the red states it is harder to come by, and it can sometimes be more substantive. That can be a model for the rest of the country. It takes time and it is frustrating, but you have to bring everybody along with you.

LAC: Let’s talk about the relationship between social movements and LGBTQ people moving to and from red states. You write, “If the dominant LGBT narrative of the twentieth century was a gay boy in the country buying a one-way bus ticket to the Big Apple, the untold story of the twenty-first is the queer girl in Tennessee who stays put.”

SA: I've had the opportunity to talk with dozens of LGBT folks about their own backgrounds, moving histories, and decisions. It's a very individual choice, and I say let 1000 flowers bloom. I meet folks who have moved to places like Seattle from a place like Kansas where they didn’t feel safe and don’t want to go back. And I totally respect that. No one should have to feel unsafe.

At the same time, I've met a lot of amazing LGBT folks who have decided to move back to or who have stayed in red states. And who say, “Yeah, it's hard, but I can make a huge impact here. I can make a lot bigger impact here than I could if I moved to San Francisco.”

Historically, we’ve needed to move, but I feel like the center of gravity is shifting. Now, more and more LGBTQ folks in the middle of the country are feeling comfortable coming out. Driven back by lack of affordability, some folks on the coasts are moving back to their old communities

A lot of LGBT people in my generation and maybe a little bit older are reevaluating their relationship to some of the places that they've left and thinking, “gosh, you know, Utah might have been scary 10 years ago, but what's what's going on in Provo, Utah now?” All of these processes are really good and helping up move toward change. And no one has to move back to a play they don’t want to go.

LAC: You recently moved to Seattle. What’s life been like for you?

SA: My wife and I moved out here in large part, because my folks retired here several years ago, and I haven't lived super close to my parents for a long time. We wanted to be closer to family. It's an interesting place for me. But what I wrote in the book still stands, I still do prefer to be queer in red states. So I don't feel like my full queer self here. The set of concerns in Seattle is very different. It's about gentrification and affordability.

It’s harder to meet other LGBTQ people than it was in Atlanta like by a hundredfold. I love being here for the natural beauty and for my family relationships, but I feel like my LGBT life is suffering, which you might not think it would in a city like Seattle. I recently got connected with the folks at Lambert House, and they're starting a series of discussion groups for LGBT youth in parts of greater King County that don't look like Seattle. I've signed up to be a facilitator.

That's how I'm trying to cope with that sort of weird isolation here. I want to go to some of the parts outside Seattle and talk with LGBT folks who don't live in the city.

LAC: I loved one of the statements you made about there being nothing more queer than getting out of your comfort zone. Can you say more about that?

SA: First, I want to say there are real dangerous threats for the LGBT community in red states. For some of us in positions of relative privilege the things that we're scared of can be scarier in our heads than they are in practice. One of the most poignant demonstrations of that for me was hanging out with Jess Herbst, former mayor of New Hope, Texas, a small town outside of Dallas [Herbst is the first openly transgender mayor in Texas history]. While I was staying with her and interviewing her for the book, we also spent a lot of time together just like hanging out around her house. We'd go to dinner and the nearby town in McKinney. We went to her city council meeting, that kind of thing.

And she talked with me very affectingly about how she was once so so scared to step out of the house. Now, she was wining and dining me in local restaurants. It used to be the case that she would only go out with a group of other trans women and take excursions to Dallas. It was really interesting to me for her to be doing something she was once so afraid to do. And then realizing, hey, like, it's actually not that big a deal.

My trip was like a long exercise in getting out of my comfort zone even though I was going back to some places that I was familiar with. Gosh, I couldn't think of a more unnerving place to start the trip than Provo where I had felt so scared and alone. I also visited really unfamiliar places like, Mississippi where I hadn't spent much time, and the Rio Grande. There's so much to be gained from from seeing more of the country.

Follow Samantha Allen on Twitter @SLAwrites and of course go buy her book Real Queer America.